It’s common sense in our field that endurance causes muscle loss, right? That was precisely my view during my PhD program in Sport Physiology five years ago. But it’s not so simple…

Let me tell you the story of a male endurance athlete. He never lifts anymore and walks around with 185 pounds of lean mass at ~10% body fat. He’s a “pretty jacked guy” at just under 210 pounds and 6’1. He’s been running and riding 5-15 hours per week and occasionally does a push-up or two for fun. Maybe once a month.

The second is a story of a female endurance athlete who has very rarely weight trained (<1 day/wk) since the end of 2014. She is 5’9, 141 lbs, at ~14% body fat, giving her a lean mass of ~120 pounds. She is very lean and more muscular than she ever was as a strength/power athlete when she was a nationally competitive sprinter and bobsled athlete.

During much of the last 3 years, both athletes have spent substantial time attempting to intentionally lose muscle! Hint: the athletes are me and Michelle, both RP 1:1 coaches.

The point of telling you these stories is not to convince you that endurance training is not catabolic. It is.

I intend to convince you of the following:

- It probably isn’t nearly as catabolic to pre-existing muscle as you once thought.

- There are specific training and diet strategies that you can take to ensure muscle retention during times of substantially increased endurance training.

- This knowledge can inform your long-term training planning.

If you’re like Michelle and I, your deeply held belief that endurance training is intensely catabolic to your present state of muscularity stems from the following:

- It just so happens that all the coaches who recommended you do endurance training while you were seeking strength/muscularity did a whole bunch of other things wrong in your programming too.

- You probably didn't know the first thing about how to fuel your weight training or eat for muscle growth back when you were also doing endurance training.

- You certainly didn't fuel well for the endurance training you were doing either, and maybe you don’t even know how now…

As a result, you were less muscular than when you optimized everything you could for muscle growth.

Optimization happened a bit later, sometime after encountering Mike Israetel or *insert other intelligent strength/lifting coach*. Turns out that elimination/reduction of cardio only played a small role in your ability to gain muscle, progressively, over time.

Other things that might have contributed to increases in muscularity:

- Consistent workout fueling, pre-, intra-, and post-workout.

- Consistently increased protein consumption. (1g/lb is great)

- Nutritional periodization, including masses, maintenance, and fat loss phases.

- 4-6 days per week of lifting, 48+ weeks per year, following a genius program (like The RP Hypertrophy app), instead of 2-4 days per week, 40 weeks per year with sub-optimal bro-science or mixed-focus programming.

- Perhaps cessation or reduction of alcohol consumption?!

- Increased attention to sleep quantity and quality!

All taken together, you might be surprised to find out that making good choices for muscularity in all other areas of your training/diet lifestyle might lead to solid muscularity in the face of also enjoying endurance training.

Most importantly, the ability to gain muscle may be hurt to a much greater degree than one’s ability to retain muscle during endurance training. That is, it’s much easier to retain muscle you already have than to gain it anew. This ease of muscle retention is what opens the door for expanded cardio or endurance training without significant losses.

The key takeaway for your long-term planning is that it might be a good idea to gain the muscle you want now, and slowly layer in more endurance now or in the future, because it’s a whole lot easier to gain, and then retain muscle during added endurance than it is to do both at the same time.

There are several key things to do right now if your goal is increasing endurance performance & maximizing muscle.

Let’s start with nutrition strategies:

- Consume 0.7-1.0g/lb protein.

- Consider moving to a slightly lower-fat diet composition.

- Make up for any reduction in fat and protein consumption with increased carb consumption.

- Always consume protein pre- and post-workout.

- If you’re training indoors, consider consuming 500-1500mg sodium per hour to prevent hydration issues. Quick info: Sodium citrate has about 1000mg sodium per tsp. Table salt is about 2000mg sodium per tsp. Add either to your workout carb beverage.

- Consider taking ~3-7g per day of creatine. Take it during or after training. Consider this most strongly if you value strength & power performance, or sprint ability.

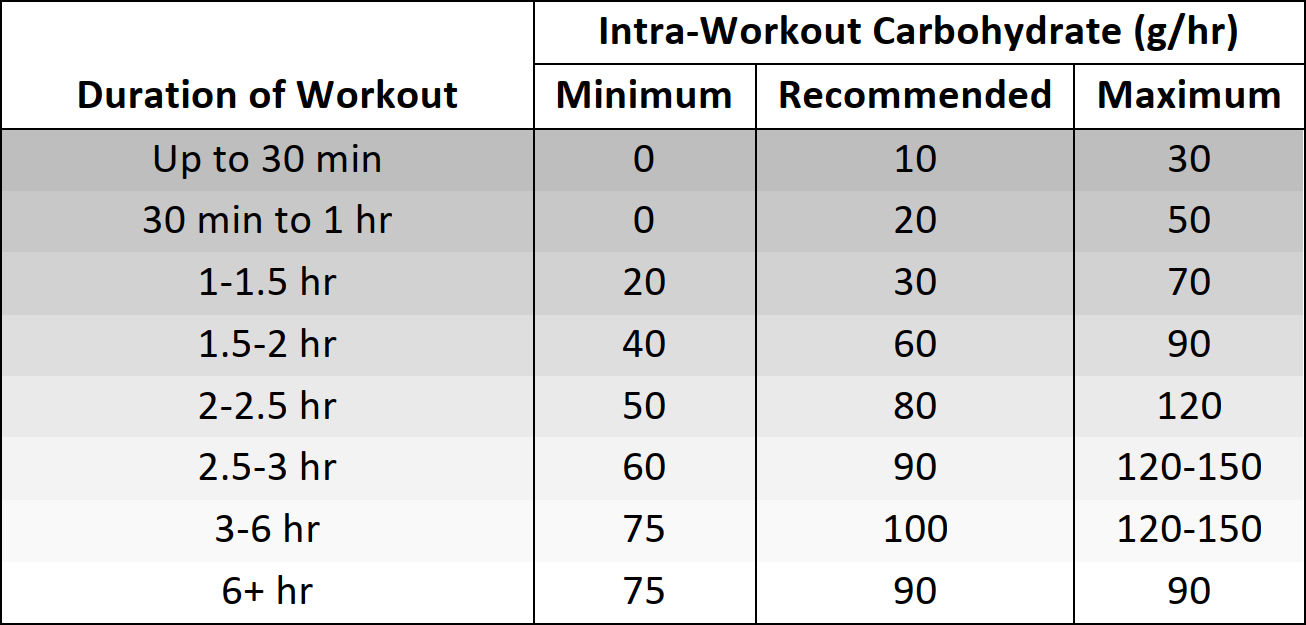

- Always fuel with carbs, pre-, intra-, and post-workout, and make sure that your fueling strategy is adequately meeting the demands of your training.

- Carb amounts needed for longer endurance work are enormous compared to that needed for more conventional lifting training. The RP Diet for Endurance is your go-to resource for knowing precisely how to do that.

(Table of endurance intra-workout carbohydrate recommendations from The RP Diet for Endurance)

And last but not least, there are several important considerations on how to structure your training and lifestyle:

- Maximize sleep. More is better. Quantity matters more than quality. Quantity is also more important than continuity. Read: naps are great if they don’t delay sleep at bedtime.

- Stay in touch with weight training but substantially reduce the volume your lifting. Keep intensity relatively high to maintain strength. Your maximum recoverable volume (MRV) is reduced in response to endurance training. Thus, training with your old training volumes might be counterproductive, when compared to more optimized-for-endurance lifting volumes.

- Keep your lifting sessions as far separated from your endurance sessions as possible.

- If you must lift in the same session or very near to your endurance work, do the one that matters most to you, first. If you care most about muscle retention or strength gain, lift first. If you care most about your upcoming triathlon, gran fond, or half marathon, do the endurance work first.

- Don’t do unnecessary high-intensity work. It’s more fatiguing and combative to muscle retention than moderate (MISS) or low-intensity (LISS) work. You can make enormous fitness gains for a long time with a large amount of just LISS and MISS work. Don’t underestimate the power of just spending hours at ~130-155bpm to increase your CV fitness dramatically, both in long stuff and in higher-intensity intervals. Doing more HIIT might do the same, but it comes with the tradeoff of massive fatigue. It’s sometimes valuable, but it should almost never make up more than half of your endurance work.

- If you’re doing multisport like triathlon, or just like doing all the things, bias your training slightly more towards less catabolic endurance work. Cycling, swimming, and/or rowing might be better options than running, which appears to be slightly more catabolic. Small shifts in frequency and volume can be meaningful!

Michelle, the story of the female endurance athlete, now trains 15-25 hours per week doing purely endurance work. She holds exactly the same level of muscularity as when she was at her strongest. Here peak muscularity was not near her genetic limit of muscularity as she had probably only accumulated ~4 years of optimized lifting alongside her other sport training.

She can now ride >20mph on a bike for 6+ hours and can run a Boston-qualifying marathon time on fatigued legs. She hasn’t lifted seriously in 6 years. If anything, in the last two years, she has gained some leg muscularity because of her extensive cycling, which neither of us wanted to admit for a long time.

If you’re like her and aren’t really at your genetic limits of muscularity, you might be able to do substantial endurance work and retain all your current muscle. You may even gain some!

For myself, I train 5-15 hours per week doing purely endurance work. I have lost ~15 pounds of muscle from my peak of 225-230 pounds at about 10% fat. At my peak, I had accumulated close to 15 years of lifting, with more than 70% of it has been reasonably intelligent and periodized. Half of that muscle loss has been intentional because I was tired of carrying muscle uphill chasing Michelle around.

I haven’t lifted in 3 years, and my weight and body composition has stabilized over the last year. It will take a concerted effort if I ever decide I would like to lose more muscle.

If you’re like me and have spent decades developing muscle mass, there will be some muscle loss with a complete move to endurance work, but I think you’ll be surprised by how little it is in the long run.

Finally, a word of encouragement to those who might read into this article and interpret that they need to lose muscle to perform well in endurance sports: that’s not true either - you just need to fuel your training well. In addition, make sure to train consistently and spend lots of hours with your heart rate elevated. You will find that your endurance ability improves dramatically regardless of weight or muscle loss.